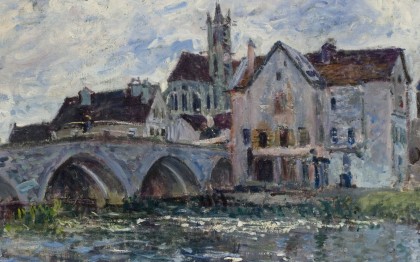

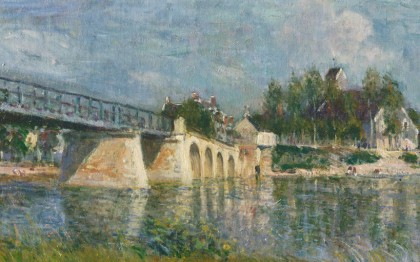

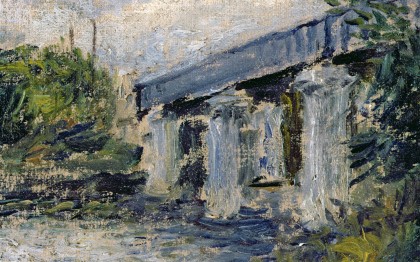

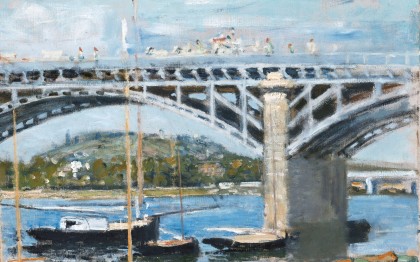

Following the tradition of the 18th century veduta, the classical motif of a bridge could only seduce Impressionist painters sensitive to atmospheric effects and reflections. With their extended format allowing a variety of viewpoints, they offered painters multiple visual solutions and incarnated both stability and dynamism. Hence Monet’s Pont d’Argenteuil, shown frontally or Sisley’s Pont de Saint-Mammès, whose diagonal line introduces a vanishing point.

Beyond these pictorial qualities, bridges, the fruit of audacious engineering, are an emblem of progress. Marking the passage from one bank to another, they can be considered a metaphor of the transition between tradition and modernity. For a movement that intended to promote a new conception of painting, where working en plain air conditioned the vision, bridges constituted a favourite motif, between air and water.

In their pictorial approach like in their subjects, the Impressionists positioned themselves as painters of modern life: at Argenteuil, Villeneuve-la-Garenne and Charing Cross, it is the steel bridge, true symbol of the Industrial Revolution, which held their attention. During the 1870s, bridges finally become a patriotic motif: after the disasters of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), their reconstruction symbolises France’s recovery.