Although landscape painters have worked outdoors from classical times onwards, their creations taken directly from nature have long been a form of note-taking or sketching to be worked up later in the studio. In the 19th century however, the status of these initial impressions become a major issue for painting: ultimately they imposed themselves as finished works and raised the practice of plein air painting to the level of a new dogma.

Over the centuries, several methods were used for painting outdoors. From the sedan chair equipped with a camera obscura to Pissarro’s wheelbarrow-easel, the idea of a mobile studio had journeyed far. In 1857, the painter Charles-François Daubigny was the first to transform a boat into a true studio. From his experience of navigation along the Oise and the Seine he drew a series of delicious prints illustrating life on board the Botin, which could evoke the adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

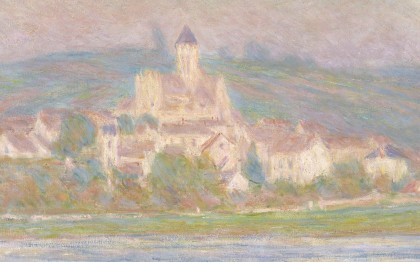

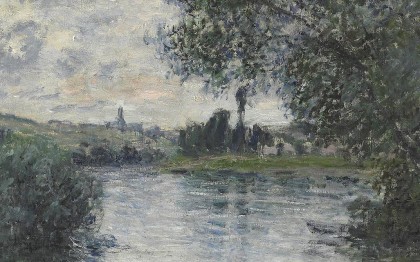

Monet followed his example in 1871 when he built a boat-studio that allowed him to paint on the Seine, as close as possible to the water. It is to this new point of view that we owe the audacious structure of the views of Vétheuil, where he stayed from 1878 to 1881 and of Lavacourt (on the opposite bank), in which the water occupies a predominant place. Back in Vétheuil in 1901, Monet applied the principle of the series of the Haystacks and the Cathedrals to the image of a small village perched on a promontory with its houses gathered around the church. But here the exercise of the series is doubled: through the variations it is as much the motif of the village as that of the reflection that we are drawn to see.