From Le Havre to Giverny, from the beginning to his final work, Claude Monet’s art is marked, more than anyone else’s, by a fascination for water and its reflections. This final section of the exhibition explores how, over the course of his career, the motif occupied a growing position, going as far as to question the classical model of landscape and the position of the horizon line, a fundamental element of Western painting since the Renaissance.

From the discovery of the laws of perspective, the horizon line traditionally structured depictions by separating the landscape into two parts. Though their respective importance could vary depending on the point of view, the most widespread model was the balance of a median position. This was Monet’s choice in his views of Etretat, created in 1883. Repeating a motif painted before him by Delacroix and Courbet, he placed the horizon exactly in the middle of his compositions.

In Venice in 1908, he retained the image of a palace floating above the Grand Canal like an apparition. The horizon line here is no longer a marker. Water, reflections, their magical shimmer and their mysterious depth occupy more space than the facades which are often truncated. In Le Palais Contarini, the horizon is placed at two thirds of the composition. The photographer, Steichen repeats this structure identically in 1913, a year after the views of Venice were exhibited at Paul Durand-Ruel’s gallery.

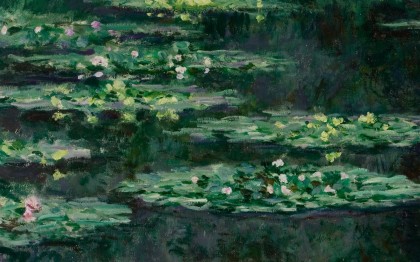

Now too old to travel, Claude Monet devoted his final years to a surprising confrontation with the water lily pond which he had had created at Giverny, exploring like nobody had done before him the possibilities offered by a mirror of water. The progressive elevation of the horizon line, until its complete disappearance, accompanies the raising of the motif in the painting’s plane, and a tilting of the point of view: Monet seems to be abandoning himself to the attraction of the reflection, which now occupies the entire composition. A photograph, taken by the artist in 1915 reveals his silhouette leaning over his favourite motif, like Narcissus in the fable.